-

To err is human

By Jane Archibald (COC Artist-in-Residence)Posted in Notes

DISPATCHES FROM THE OPERA WORLD

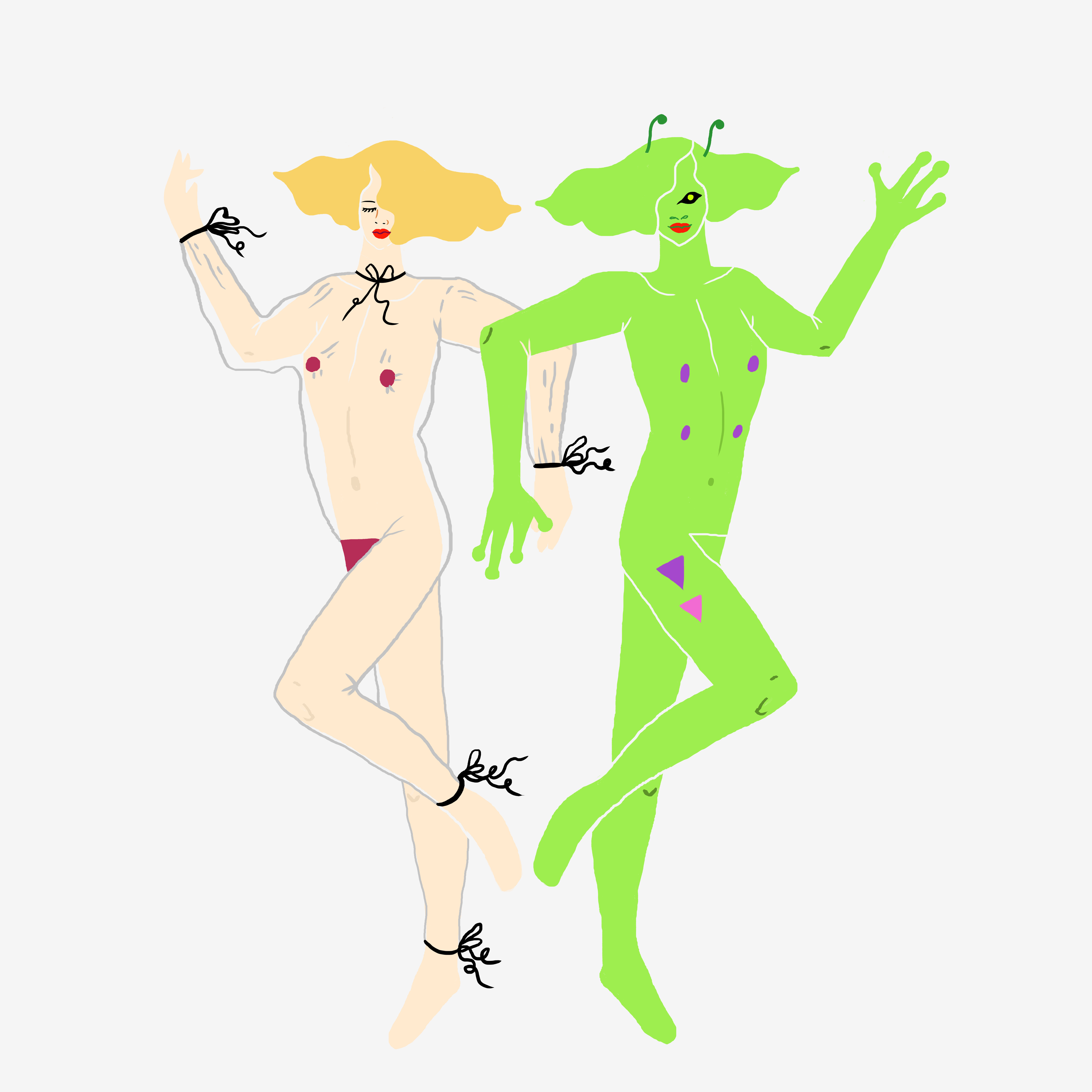

Jane Archibald, illustration by Arpanaa Das

Guest Writer

SOPRANO JANE ARCHIBALD

“To err is human,” as the saying goes, and opera singers are as human as anybody else, despite attaining Olympian high notes. In this issue, our Artist-in-Residence reflects on the surprisingly liberating experience of making mistakes on stage, as well as the seemingly unavoidable blight of all live performers: the wardrobe malfunction. New in this issue, we’ve teamed up with Toronto-based visual designer Arpanaa Das for a series of illustrations inspired by Jane's stories.

“My favourite thing is when a mistake happens.”

Apparently I said this in an interview with the COC last year when discussing the unique conditions of live performance. I don’t remember saying it, but it sounds like me!

And while it might seem an odd thing to say, it’s true.

The thing that I find so wonderful and liberating about an opera performance is its impermanence. It is a temporal experience of art, transforming moment to moment, refusing to become a fixed artifact. You can’t stop to examine it like a painting or sculpture; you just have to savour it as it goes by.

Mistakes happen all the time—it is a testament to the focus and professionalism of artists that these moments rarely detract from the impact of a performance and, in fact, can propel the energy on stage toward an even more impressive product.

The thing that I find so wonderful and liberating about an opera performance is its impermanence. It is a temporal experience of art, transforming moment to moment, refusing to become a fixed artifact. You can’t stop to examine it like a painting or sculpture; you just have to savour it as it goes by.

That is true for both us performers and the audience members. Once the conductor brings that baton to life, the plane has taken off, so to speak, and there is no getting off until we land at the end of the opera!

And for those of us on stage, mistakes… well, they just keep us on our toes and remind us (once we get over the burst of adrenaline that accompanies the realization that we’ve just royally messed up) that we’re actually not curing cancer or creating world peace—we’re simply human beings having fun and creating art.

A mistake has a wonderful way of shaking out the tension we didn’t know was there, of easing up on that instinctive tendency to pursue perfection, and of simply reminding us to be present in the moment. It connects us with our own humanity, and that makes us more compelling performers, even if our mistake is not perceptible to the audience.

I have been trying to think of some examples of mistakes I have experienced to illustrate my point. Behold, my shorthand list:

- Finger-up-nose Figaro, Toronto

- Cleopatra topless recit, Paris

- Workin’ with a merkin, Geneva

- Lamp sconce falling off wall, Met Fledermaus premiere

- Being dropped when dead, Hamlet at the Met

- Corpsing in Aix: Pedrillo making up random text in the vaudeville

- Forgetting flowers opening night of Arabella at the COC

- Tripping curtain call, Queen of the Night, Vienna

- Word mistakes… basically all the time

Just that point-form list makes me laugh, but let me elaborate on the first three.

1. Finger-up-nose Figaro, Toronto

This one gets hauled out pretty regularly when I’m at the COC because it happened during a performance of The Marriage of Figaro on stage at the Four Seasons Centre in 2016. It was in Act II during Cherubino’s famous aria “Voi che sapete” and the staging was fairly sensual—both the Countess (the divine Erin Wall) and Susanna (yours truly) were basically taking turns vying for Cherubino’s attention, kissing and stroking him, sometimes simultaneously.

At this moment, we were kissing Cherubino (the incredible performer Emily Fons) on either side of his face. Needless to say, hands were wandering, eyes were closed and, before I knew what was happening, I felt Erin’s pinky finger lodge itself firmly in my nostril!

“Before I knew what was happening, I felt Erin’s pinky finger lodge itself firmly in my nostril.”

I could sense her vibrating with laughter, as was I, and I can tell you that the self-control it took for us both to carry on as though nothing had happened was extreme. Emily was blissfully unaware (luckily for her, since she was the one singing at that point) and I doubt anyone but the most eagle-eyed observer would have noticed. But neither Erin nor I will ever forget it!

2. Cleopatra topless recit, Paris

I was singing Cleopatra in Handel’s Giulio Cesare at the Paris Opera, at the gorgeous Palais Garnier, conducted by Emmanuelle Haïm. I had been fighting a bad bug and it finally got the better of me the day before the final performance. As often happens with complicated stagings, they asked me to act the role while a last-minute replacement (the remarkable French soprano Sandrine Piau) sang the role from the side.

This is never fun, but the show must go on.

That being said, this was a production in which Cleopatra’s bare breasts are almost constantly on display. The costumes were all made of filmy gauze, designed to be entirely see-through, and at least one had no covering on top at all.

I have done a few productions in my career that were very revealing and I have normally found it strangely liberating to do so. I would never do it in real life, but, in character, to play at being an exhibitionist can be a lot of fun.

And, honestly, there is so much to think about on stage, there’s no time to get self-conscious. The physicality of singing is only about 50% of what exhausts singers during a performance; maintaining a state of being totally on-the-ball and thinking about ten different things at once, constantly adjusting, takes up all of your headspace!

But what happens when you take the singing completely out of it? Suddenly you have a lot more time to focus on feeling the cold air of the theatre on all the skin that’s exposed. You suddenly notice that things that are normally contained in well-designed support garments are free to bounce about with great abandon.

I had just literally run on stage for a scene, as directed, (if you’re a woman, you can imagine what running on stage feels like, sans brassiere) and was somewhat distracted with this new awareness of being very exposed in a way I hadn’t noticed during any of my sung performances. And instead of the recit, there was excruciating silence. I was ready to mouth the words, but no words came! I glanced to the side to see Sandrine looking panicked as she flipped pages in her score!

“I was ready to mouth the words, but no words came.”

Somehow, she had not been given the page of recitative for that scene. When it became clear that she didn’t have the music (all this happened in a matter of seconds, by the way, though it felt like an eternity) I croaked out the lines of recit myself and the show went on! It at least allowed me to confirm to myself that I was indeed not in any shape, vocally, to sing the whole opera. It shook me out of my self-consciousness and made me lighten up and proceed through the rest of the show with a more light-hearted, “what can you do!” attitude.

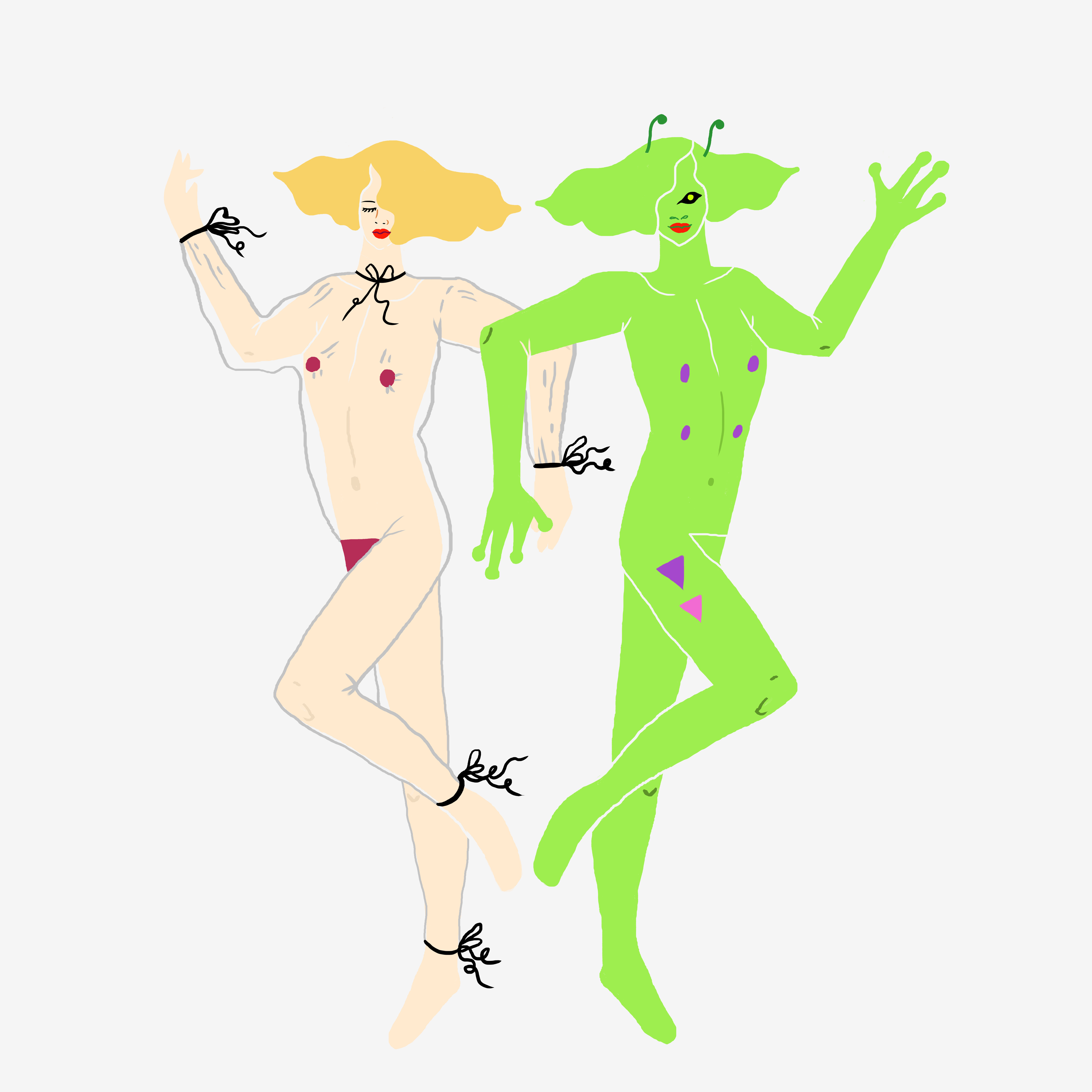

3. Workin’ with a merkin, Geneva

Yes, you read that right.

Merkin.

Nobody told me in university that merkins would play a role in my opera career.

Never heard of a merkin? Check this out and come back to us—we’ll wait.

So, I’m in a cab on the way into Geneva from the airport to start rehearsals for a new production of The Magic Flute at the Grand Théâtre de Genève. But I get a call from my agent asking if I would jump in that very evening in another production at the theatre: they need an Olympia in Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffmann.

“How convenient that I’m in town and have the role all ready,” I think. “A little bonus cash in my bank account.” So I tell the cab driver to take me straight to the theatre and I meet with the necessary people to get a crash course in the staging for that evening.

Then I head to the dressing rooms for a costume fitting. And this is the “costume” I am presented with:

Olympia costume

Now, I’ve already agreed to sing that night, so I have very little time to make my peace with this scrap of netting, two rubber nipples, and the aforementioned merkin.

At least there are lovely black ties at the wrists and neck… to make me feel less exposed? In this production, Olympia is a sexdoll (of course she is—what else!).

In any case, later that day, I find myself in the costume, on stage doing Olympia’s little dance, the attached merkin and rubber nipples shifting as the stretchy netting of the bodysuit moves around.

And when I glance down at the end of the aria, having danced and wiggled my way through the scene?

I see that the merkin has migrated down and to the left and has come to rest on my leg (thankfully I was allowed some underwear under the bodysuit!). The rubber nipples have also shifted and are no longer covering my own (so now there are four!); Olympia now looks more like a science experiment gone wrong than a sex doll!

Nothing to be done about it, I just continue the scene and have a good laugh as I accept my jump-in fee!

“When I glance down at the end of the aria... Olympia looks more like a science experiment gone wrong.”

After my last NOTES contribution, the COC apparently got a lot of great feedback from readers and several questions emerged about language, including:

(a) how many languages do you speak?

(b) in how many languages do you sing?

(c) how hard is it to sing a language in which you’re not necessarily fluent?

These are great questions! Facility with language is such an important part of the skill set we need to develop in this career. It’s easy for us singers to forget that, for most North Americans, the foreign language aspect of opera can be an intriguing, if not intimidating, aspect of this art form.

In Richard Strauss’ Arabella, Jane (right) sang and spoke in German. This winter she continues with the Teutonic tongue in Mozart’s German singspiel, The Abduction from the Seraglio, while in the spring she’ll show off her Russian in Stravinsky’s The Nightingale and Other Short Fables.

(a) how many languages do you speak?

I feel I can say with confidence that I speak three languages (English, French, and German). English, of course, is my mother tongue. I still make a lot of grammatical mistakes in the other two, but I can converse with relative ease, make myself understood as needed and, with the occasional request for help with a word or two, do my job in any of those three languages (including discussing the staging/music, character development, interviews, etc.). I am embarrassed that I don’t have Italian on that list, but I simply have not sung in Italy much, and my career has been lighter on Italian repertoire up to this point. Those factors make a huge difference in learning a language and gaining confidence.

(b) in how many languages do you sing?

Singers perform in many languages, even if they are not able to converse in all of them, and they have to make sure they understand exactly what they’re saying, as well as what all the other characters are saying. My repertoire currently includes roles or pieces in English, French, German, Italian, Latin, Russian (and Czech, if you count a small cover assignment from my 20s).

(c) how hard is it to sing a language in which you’re not necessarily fluent?

Well, there’s no question that it is more difficult. First, it’s simply more prep work to translate the entire score. If you speak the language, then that entire step is eliminated, saving hours of work. Plus, if you don’t speak a language, a lot more time is required to study the text so that you really know it without a second thought, without looking at your score or searching your memory. This is important so that you can sing in a way that conveys deep understanding of every word, even while you’re simultaneously focused on the other myriad musical or staging issues going on in a given second. Even with that level of preparation, there’s no arguing that translating cannot compensate for actually speaking a language, because the latter allows for a different, much deeper level of understanding.

All illustrations by Arpanaa Das. All production photography by Michael Cooper. Photo credits (top to bottom): Erin Wall as the Countess, Emily Fons as Cherubino and Jane Archibald as Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro (COC, 2016); image of Olympia costume courtesy of Jane Archibald.