-

Madama Butterfly Listening Guide

By Kiersten HayPosted in Madama ButterflyBy Gianmarco Segato, Adult Programs Manager

Introduction

Puccini’s Madama Butterfly is generally considered one of the greatest works to emerge from the Italian verismo movement – that is, the short, concentrated period in operatic history which lasted from just 1892 (the premiere of Catalani’s La Wally) through 1926 (when Puccini’s Turandot marked its end). Verismo was the Italian response to the naturalist movement that originated in French literature, notably in the working-class milieus presented by Émile Zola and Guy de Maupassant. Italy found its equivalent in Giovanni Verga, author of the short story Cavalleria rusticana on which composer Pietro Mascagni based his 1890 verismo-defining opera of the same title.

Despite its origins in “realism” with stories based on contemporary, working-class life, the operatic iteration of the verismo movement soon shifted focus to explore more diverse subject matter which embraced the “exotic.” Consider this list of verismo heroines who emerged in the decades after 1892: noblewomen (Giordano’s Fedora; Cilea’s Gloria; and, the nobly born nun Angelica in Puccini’s Suor Angelica); courtesans (Stephana in Giordano’s Siberia; Puccini’s Magda in La rondine) and "oriental waifs" (Mascagni’s Iris and Puccini’s Liù in Turandot). So, it is an oversimplification to view verismo opera as dealing solely in subjects drawn from tawdry newspaper headlines (as did Verga’s and Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana). The proof is in Madama Butterfly, only the most famous example of how composers of this era, including Mascagni, strove to constantly expand and refine their art, searching for new and original subject matter to include such (then) “exotic” cultures like Japan’s.

Musical Excerpt #1

Act II, Aria: “Un bel dì vedremo” (“One fine day we’ll see”)

Connection to the Story

It has been three years since Butterfly’s husband, Pinkerton, left Nagasaki and only her maid, Suzuki, has stayed with her. The two women are desperately poor but Butterfly is content to remain in the house and wait, convinced that her husband will return.

Musical Significance

“Un bel dì” is arguably the most recognizable aria in the entire operatic repertoire. While it is easy to be swept away by its intoxicating melody, this aria is much more than a pretty tune: its musical structure is complex and sheds light on Puccini’s skill in modifying Japanese musical style, blending it with the harmonic structure of the Western tradition. The opening melody in which Butterfly affirms her belief that Pinkerton will return is firmly within the realm of traditional Western harmony. This mirrors Cio-Cio San’s self-identification as an “American wife” who lives in what she calls an American house. There is a shift in the harmonic language at 1:15 however on the words “Io non gli scendo incontro. Io no.” (“I won’t go down to meet him. Not I.”) Here, the melodic pattern is inspired by what is believed to have been Puccini’s favourite Japanese tune. Then at 1:32, the Japanese Yang scale is heard while Butterfly sings “e aspetto gran tempo e non mi pesa, la lunga attesa” (“and wait for a long time, but I won’t mind this long waiting”). In both of these phrases, Puccini purposefully incorporates the more open tonality associated with Asian music to reveal that Cio-Cio San has never abandoned her Japanese identity. The composer copied and studied melodies from publications that contained transcriptions of Japanese songs. He also listened to records shipped from Tokyo. It is significant that Puccini inserts these melodies precisely when Butterfly exhibits what is, from a Western perspective, stereotypical Japanese female behaviour: reticence and patience. Musically, it is proof that despite her attempts to Westernize she does not become an American after all.

Musical Excerpt #2

Act I: “…E soffitto e pareti…” (“…And the ceiling and the walls…”)

Connection to the Story

Lt. B. F. Pinkerton of the US Navy, stationed in Nagasaki, Japan, is being shown the peculiarities of the Japanese house which he has just bought. He is joined by the US Consul, Sharpless, for drinks.

Musical Significance

In the decades around 1900, the business of writing Italian opera had never been more difficult. The various traditional forms and situations that had sustained the genre through most of the 18th and 19th centuries had lost their significance: each work now had to define a unique aesthetic world. This new drive to discover the “exotic” inspired Puccini to search for subjects marked by some aspect of local colour which possessed a readily applicable musical connotation. For Madama Butterfly the result was a unique conflation of Eastern and Western musical traditions which introduced Puccini’s audiences to Japanese culture and music. This intriguing mix is introduced right from the start: the opera begins with a fugue (a composition in which a short melody or phrase is introduced by one part and successively taken up by others), one of the strictest musical forms in the Western tradition. The agitated, yet structured nature of the fugue immediately communicates American efficiency as Lt. Pinkerton surveys his new abode and servants scurry around, showing off its amenities. Puccini’s use of the fugue also served as a challenge to critics who questioned his harmonically advanced style. He may have felt the need to show off his “learnedness” and mastery of a traditional form before (almost immediately) heading into more musically progressive waters. This can be heard at 1:09 where, the very “Western”-sounding fugue is immediately followed by our first encounter with the more open harmonies Puccini uses throughout the opera to conjure a Japanese setting. One technique used by Western musicians of this period was to incorporate pentatonic scales (five notes per octave in contrast to the Western eight-note scale) which they associated with a rather broadly defined and exotic East.

Musical Excerpt #3

Act II: “Ebbene, che fareste, Madama Butterfly…E questo? E questo?” (“Well then, what would you do Madam Butterfly…And this one?”)

Connection to the Story

Sharpless asks Butterfly what she would do if Pinkerton were never to come back. She is appalled at the suggestion and brings in her son for him to see.

Musical Significance

In this brutally honest, emotionally raw scene, Sharpless strips away any final illusions Butterfly might have of an idealized “American” family life with Pinkerton. Her response is equally blunt as she asks her servant Suzuki to quickly escort “his Honour” from their home. The mood of the scene is brilliantly conveyed by Puccini’s orchestration – listen at 0:52 to the low strings as they ominously creep up the scale starting softly, gradually increasing in volume, mirroring the increasing tension between Butterfly and Sharpless. The expanded use of orchestra is a defining feature of verismo opera – Puccini looked beyond the Italian tradition to other national schools, especially the German. The question of Germanic influence was a controversial subject in Puccini’s time and to confuse matters, he left clues supporting both sides of the issue. He was quoted as saying: “I am not a Wagnerian; my musical education was in the Italian school” but also remarked, “Although I may be a Germanophile, I have never wanted to show it publicly.” Whether or not Puccini wished to associate himself with Wagner, it is clear that the sound world of the Italian’s operas are miles away from the relatively understated, sonically less extravagant bel canto opera (the world of Donizetti and Bellini).

This excerpt also highlights one of verismo’s other distinguishing musical features: its reliance on short, simple yet overwhelmingly grand vocal climaxes to trigger emotional reactions in the listener and to define character. Listen at 2:41 to the grand orchestral fanfare with Cio-Cio San in full-cry, revealing to Sharpless that she has borne Pinkerton’s son (“E questo” – “And this one”). The vocal line here consists of a simple repeated rising interval, yet its placement in the soprano’s upper register and the richness of the scoring beneath it communicates intense emotion. The passage is powerful, heart-wrenching and musically concise. No lengthy aria is required to communicate a myriad of ideas and feelings: that for Butterfly, this triumphant moment represents the trump card which will ensure Pinkerton’s return yet we (through Sharpless) cannot help but be filled with an underlying sense of foreboding.

Musical Excerpt #4

Act II, Aria: “Tu? Tu?...Piccolo iddio!” (“You? You?...My little god!”)

Connection to the Story

As Cio-Cio San is about to commit suicide, her maid Suzuki pushes her child into the room. Butterfly says goodbye to him, blindfolds him, and leaving him to play, goes behind a screen to kill herself.

Musical Significance

This aria marks the emotional climax of the entire opera. It is also the only moment in which Butterfly expresses herself entirely in a Western idiom without the addition of either authentic, Japanese folk tunes or Puccini’s manufactured “Japanese” melodies. She sings directly to her son in a tonal key based on a harmonic minor scale (one of the basic building blocks of Western music harmony). The implication seems to be that in killing herself, she is freeing her son of his Japanese identity (his father has returned to Japan with his American wife to claim his offspring), and so, for the only time in the opera, she is given music free of Japanese associations. In the aria’s postlude however, after we hear Pinkerton’s all-too late cry of “Butterfly, Butterfly,” Puccini purposely resorts to the Japanese folk tune which recurs throughout the opera (listen at 3:38). By committing suicide, Cio-Cio San in fact embraces her Japanese identity, preferring to die with honour than face the shame of being husband-less and giving up her child. Then, in a bold modernist move, Puccini ends the opera on a screaming, unresolved chord (4:25) thereby flouting one of Western music’s strictest rules - indeed, its most basic one - that of final tonal resolution (the listener’s ear is not given the satisfaction that musically at least, the piece has reached its final resting place). This brief brush with atonality not only suits the tragic conclusion but also acts as the final, conclusive break between mother and son; life and death; West and East.

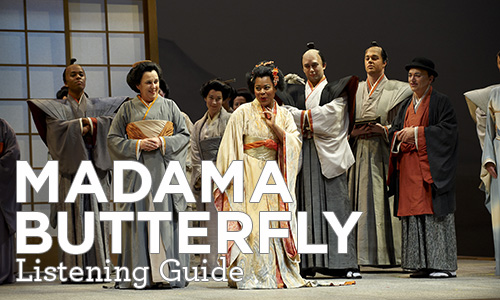

All tracks listed are excerpted from Madama Butterfly, Decca 452 594-2. Orchestra and Chorus of the Accademia di Santa Cecilia, Rome, Tullio Serafin, conductor. Renata Tebaldi, Carlo Bergonzi, Enzo Sordello. You can also experience the Listening Guide online at COC RadioPhoto: (banner, left-right) Justin Welsh as Yakuside, Lilian Kilianski as Cio-Cio San's Mother, Yannick-Muriel Noah as Cio-Cio San, Michael Uloth as The Imperial Commissioner, Neil Craighead as The Official Registrar and John Kriter as Goro in the Canadian Opera Company's production of Madama Butterfly, 2009. Photo: Michael Cooper