-

Your COC1819 Summer Reading List

By Nikita GourskiPosted in 18/19

This summer, whether you’re lounging in a Muskoka chair or jostling for space on the TTC, here’s a radical idea: put down the phone, unplug, and crack open a great book. (Reading! Remember that?) We’ve prepared a list of excellent reads that will also get you ready for COC1819, featuring titles that inspired the operas of our upcoming season.

EUGENE ONEGINEugene Onegin by Alexander Pushkin, translated by James Falen

If the phrase “novel-in-verse” doesn’t exactly pique your interest, that’s understandable. But Pushkin’s poem is an absolute gem that deserves your attention – and it’s one of the few masterpieces of world lit that can be read in one-ish sitting.Set in 1820s Imperial Russia, we meet Eugene Onegin, a young dandy who is bored by the endless parties and debutante balls of St. Petersburg. When his wealthy uncle dies, Onegin moves to the country, where a young woman from another estate, Tatyana, falls in love with him and declares her feelings in a heartfelt letter that is the basis of a key musical moment in Tchaikovsky’s opera. Cruelly, Onegin only doubles down on his carefully curated persona, and lectures Tatyana on the inevitable disappointments of marriage and the dangers of unguarded emotions. Something of a 19th-century mansplainer, Onegin reveals himself to be more concerned with projecting a world-weary image than recognizing the courage of emotional vulnerability.

Duels follow! There’re dramatic reversals of fortune, layers of literary allusion, and plenty of sharply observed social detail – all written in a unique pattern of rhyme and metre that has been all-but-impossible to translate into English; it’s led more than a few scholars down decades-long rabbit holes and broken friendships along the way.

But even if no translation can capture Pushkin’s musicality, James Falen’s 1990 version is a standout that honours the lilting structure of the original while still preserving literal accuracy:

“My uncle, man of firm convictions...By falling gravely ill, he's wonA due respect for his afflictions --The only clever thing he’s done.May his example profit others;But God, what deadly boredom, brothers,To tend a sick man night and day,Not daring once to steal away!And, oh, how base to pamper grosslyAnd entertain the nearly dead,To fluff the pillows for his head,And pass him medicines morosely --While thinking under every sigh:The devil take you, Uncle. Die!”

Charming guy, that Onegin.

HADRIANStorytelling about ancient Rome can run the risk of becoming a kitschy parade of leather sandals, toga-clad senators, and gladiators doing battle in amphitheatres. But, in truth, the period was actually bursting with social, cultural, and economic activity so significant that we still see and feel its echoes in our world. To restore the rich detail and vivid particularity of the Roman period, start with these books that – in completely different ways – venture inside the heart and mind of one of Rome’s great rulers.

The Memoirs of Hadrian by Marguerite Yourcenar, translated by Grace Frick

This work of historical fiction is told from Hadrian’s point of view as he writes a long letter to his successor, Marcus Aurelius, meditating on his accomplishments and failures, his deep love of Antinous, and the central role of art and imagination in his empire. The philosophical tone of the novel, its stately pace and form, give rise to an engrossing character study of a ruler navigating the twin poles of the personal and the political implications of life and legacy.

These millions of lives past, present, and future, these structures newly arisen from ancient edifices and followed themselves by structures yet to be born, seemed to me to succeed each other in time like waves; by chance it was at my feet that night that this great surf swept to shore. . . . The massive reef in the distance, perceptible in the dark, that gigantic base of my tomb so newly begun on the banks of the Tiber, suggested to me no regret at the moment, no terror nor vain meditation upon the brevity of life.

Hadrian and the Triumph of Rome by Anthony Everitt

Whatever the details of the boy’s origins and social status, the large, the overwhelming fact is that Hadrian fell in love with Antinous. The relationship was to color the rest of their lives.As a counterpoint to Yourcenar’s fictionalized account of Hadrian, Everitt’s work offers a more straightforward biography, scholarly and objective in its aims. Everitt is a brisk and accessible guide to the Roman period of second century AD, carefully charting how Hadrian’s key ideas – curbing imperial expansion and injecting Greek cultural values and practices into Roman society – played a major role in reshaping the fate of the Roman empire.

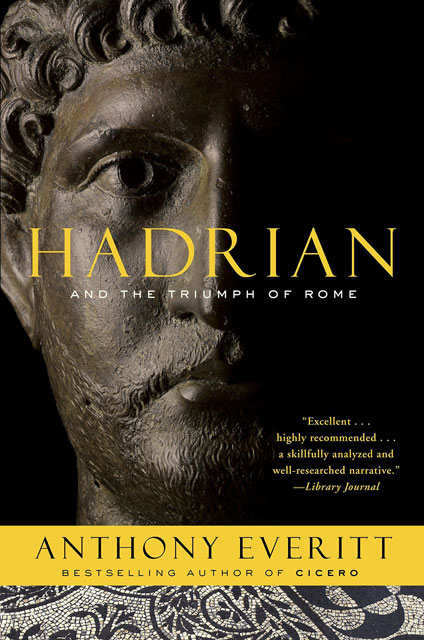

ELEKTRAElektra by Sophocles, translated by Anne Carson, available as part of An Oresteia

Richard Strauss’ opera Elektra was based on a play by Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Elektra, which was based on the ancient Greek tragedy by Sophocles, also called Elektra. (Stay with us, there will be more Elektras before this recommendation is finished.)With his play, Hofmannsthal zeroed in on a key story from Greek mythology – Elektra’s killing of her mother Klytämnestra in retribution for the murder of her father Agamemnon. But while he drew inspiration from Sophocles, Hofmannsthal retells the myth from a distinctly modern place, where new theories of psychoanalysis, the unconscious, and dream images hover over the ancient, mythological characters.

But to get into the spirit of Western literature’s most dysfunctional family as a reader, we recommend going the way of Anne Carson, the brilliant Canadian poet, translator, and classicist best known for genre-defying work like Autobiography of Red. Her no-holds-barred translation of Sophocles’ Elektra has its share of detractors, but in favouring plain language over the elevated poetic register, Carson distills the horrors of the House of Atreus down to their primal force:

You are some sort of punishment cagelocked around my life.Evils from you, evils from himare the air I breathe.

COSÌ FAN TUTTELorenzo Da Ponte: The Life and Times of Mozart’s Librettist by Sheila Hodges

Ok, you got us – this Mozart opera was not based on any specific literary source, but it does constitute the final installment in Mozart’s fruitful collaboration with the poet Lorenzo da Ponte.In addition to Così, da Ponte also penned the words for Don Giovanni and The Marriage of Figaro. But it’s Da Ponte’s own life that’s filled with enough wild adventures to make it excellent summer reading. His Jewish father converted to Catholicism shortly after Lorenzo was born to provide his children with the best possible education, which usually meant a local seminary and a life in the clergy. But while da Ponte was a brilliant student, the self-denial of priesthood wasn’t for him – six months after being ordained, he decamped for Venice and the whirlwind pleasures of gambling and romantic flings.

Da Ponte’s time in “the City of Water” was gloriously scandalous: he lived with knife-wielding mistresses, played the fiddle in brothels wearing his priest’s garb, and seduced married women. His run-ins with the law over his subversive poetry only endeared him to the rich, liberal-minded upper class who hired Da Ponte as a secretary or tutor for their children. During this period he also flourished as an improvvisator, the Italian 18th-century name for what was essentially freestyle rapping; here, a poet would weave lines of verse on any given topic to musical accompaniment for the amusement of rich patrons.

Da Ponte was eventually banished from Venice and found his way to Vienna. There, he used his charm and wit to smooth-talk Emperor Joseph II into giving him the job of in-house poet at the recently established Italian opera company in the city. The rest isn’t so much history as an ever-more-astonishing series of events that would see da Ponte collaborate on Mozart’s most famous works, face banishment again (this time from Vienna), immigrate to America, run bookstores and grocery stores in New York City, teach at Columbia University, and play an integral role in bringing Italian opera to the United States. With material this good, it’s no wonder that there’s no shortage of biographies on da Ponte – including his own self-congratulatory memoir.

But the best in a patchy field is Sheila Hodges’ Lorenzo Da Ponte: The Life and Times of Mozart’s Librettist, which is meticulously researched, beautifully written, and an excellent exploration of the collaborative artistic process that yielded the Mozart-Da Ponte trilogy.

LA BOHÈMEThe Bohemians of the Latin Quarter by Henri Murger, translated by Ellen Marriage and John Selwyn

Living hand-to-mouth in 1840s Paris, the novelist and poet Henri Murger produced a series of short stories that drew on his personal experiences as a struggling artist in the Latin Quarter.Though well-received when they first appeared in serial form in magazines, the stories exploded in popularity after being presented as a stage play adapted by Théodore Barrière, co-written with Murger. The show’s wild success launched Murger, only 27 at the time, into literary stardom – Victor Hugo congratulated him in writing, a major publishing house courted him with a book deal, and France’s highest honour, the red ribbon of the Légion d’Honneur, was eventually presented to the once-starving poet.

Murger’s stories gave us the archetype of young artists in a cosmopolitan city: fraught with money worries, fluid in their love lives, and committed above all else to their art versus the prospect of selling out. The spirit of Murger’s stories inspired not only Puccini’s La bohème, but was once again transplanted, this time to 1990s New York for Jonathan Larson’s immensely popular musical Rent.

...these young men had laid down as a first principle of their association that they would never forsake the higher walks of their art; that is to say, that in spite of the poverty of their mortal lot they would none of them bow to Necessity. Thus the poet Melchior would never consent to lay aside what he called his lyre to write a commercial prospectus or a topical pamphlet….

Othello by William Shakespeare

OTELLO

Legend has it that Verdi always had two books by his side when travelling: the Bible and the collected works of William Shakespeare.

Verdi didn't read English himself but benefitted from his wife’s knowledge of the language and, unlike many of his contemporaries, he wasn't satisfied with using indirect sources in adapting Shakespeare, preferring instead to get as close to the text as possible through meticulous cross-referencing of existing translations.

Othello is exquisite in dramatizing how jealousy alters perceptions. It gives linguistic shape to the psychological stressors faced by Othello in being both a highly esteemed general as well as a person of colour in predominantly white Venetian Republic. Of course, it also produces one of the most inscrutable and cunning theatrical villains, the odious Iago:

But I will wear my heart upon my sleeve

For daws to peck at. I am not what I am.

Finished reading and ready to check out the operas? Discover our electrifying 2018/2019 season.

Take your culture game to the next level with our monthly eOpera.