-

Get to Know: Vivian Fung

By COC StaffPosted in A Season Like No Other

In November 2021, JUNO Award-winning composer Vivian Fung premiered new work at the Edmonton Opera. The two scenes, Grover and Friends and Alarm, are based on her family’s history of fleeing the Khmer Rouge and escaping Cambodia in the 1970s. Although Fung and her parents were living in Alberta at the time, she reflects on how the experiences of her extended family on the other side of the world had a profound effect on her childhood, and continue to affect her family dynamics to this day.

As part of the Canadian Opera Company’s Showcase Series for Asian Heritage Month, we were able to interview Vivian to learn more about her life, her process, and her plans for the future of the work.

COC: When did you start composing?

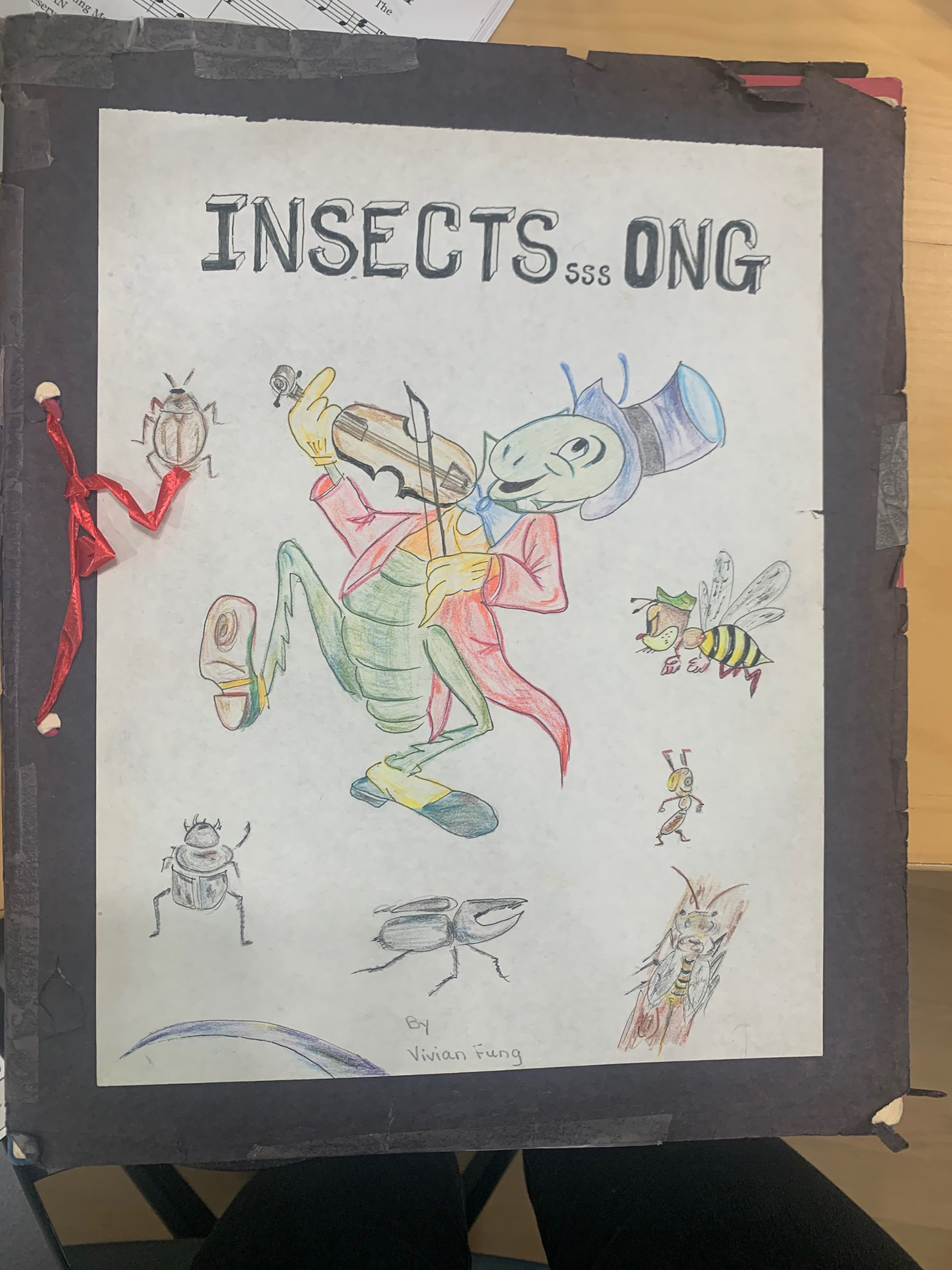

Fung: I was born and raised in Edmonton, which is where I began my musical journey. I was really young when I began composing, maybe 7 or 8. My mom got me started in piano very early but I hated practicing, so I started playing around with composing my own music instead of practicing my piano homework. My first piano teacher Helve Sastok was a composer and when she found out what I was doing she really encouraged me. She taught me how to notate, so I continued to write my own pieces. InsectSSsssongs is one of my first compositions—a series of short works themed around different bugs.

COC: Your work, Grover & Friends, is about your family’s experience during the Cambodian Genocide—a history you have only learned about more fully as an adult. Why do you want to tell this story now?

Fung: As you age, you look back on your life and you wonder about how you grew up and why things happened; why my family had certain idiosyncrasies. I felt like I wanted to understand my family to understand myself. Around this time, my cousin passed away from suicide and it really instilled a desire to learn about my extended family. The year they were ousted by the Khmer Rouge was the year I was born. As you can expect, although I wasn’t in Cambodia, it shaped my entire childhood and my relationship with my parents. My mother was very protective of me, all because of having to witness what was happening to her family on the other side of the world. As an adult, I now understand that experience as part of the cycle of trauma. I want to share this very personal experience because it resonates with a lot of people—those who have experienced the trauma first hand, and those who have generational trauma within their family.

COC: What was it like visiting Cambodia for the first time? What aspects of that experience are present in Grover & Friends?

Fung: Travelling opens up new worlds. You can do research, but nothing is like going to a new place. You can really get a sense of what happened when you visit landmarks or places such as the Tuol Sleng Genocide Musum—it is still palpable. It was my uncle, my mother’s brother, who was there during that time. His wife ran a midwife hospital in Phnom Penh and we were able to locate the old building. It was so important to me to witness my mom discovering the hospital, and seeing her reactions to revisiting this place.

COC: Can you talk about the perspectives present in your scenes? What moments or feelings are you trying to capture?

Fung: The piece is a collaboration between myself and my librettist, fellow Albertan, Royce Vavrek. I worked to compile oral history in the form of emails from cousins and aunts and uncles, asking them questions about growing up and life in Cambodia, their memories from during that time, etc. A lot of it was really stream-of-consciousness, but Royce has this beautiful ability to absorb these ideas in a very sensitive, meaningful way. The scene you see in Grover & Friends is of a cousin who came to Canada following their escape from Cambodia. She is trying to learn English by watching Sesame Street, but she is distracted by a feeling that the Khmer Rouge are still coming, and they’re going to be able to come through the TV to get her. The title, Grover & Friends, seems innocent but I’m using it to really connect with the anxiety of that time.

COC: The percussion in the piece uses a lot of non-traditional instruments, such as ceramic cups and glass bowls. How did you choose these items and what sort of meaning do they have to this story?

Fung: I’m fascinated with the timbre of homemade instruments—they’re slightly out of tune; there is this otherness to them that I really like. A lot of my study and interest in this comes from Gamelan music. A number of years ago, I joined a Gamelan group that toured Bali. The culture of the artform, the temperament, the tuning systems, the way you learn music, is all very different from what I was used to. I learned a lot outside of my western composition frame of reference. These traditions inspired a lot of pieces. I feel the instruments present in my works evoke this feeling of otherness without truly representing any one specific place.

COC: What do you hope audiences take away from the piece?

Fung: Although the Cambodian Genocide happened a number of years ago, you see geopolitically with what is happening in current events, this story is very relatable to other communities all over the world. When you read about refugees in the news they can often become just a number or a statistic—a certain number of people have fled or a certain percentage of the population has been displaced. I want to show the human side of it. I don’t even really see my family’s history as a history of refugees because there is so much more to the story than that.

I hope that other people can get some understanding about what a family has been through and to feel empathy for that experience. I see myself not just as a composer but a humanist, speaking about the human condition. How an experience such as this can leave a family with trauma, and how that can affect generations.

COC: You are planning on continuing your research. Can you tell us what you will be focusing on next?

Fung: My next step would be to return to Cambodia, in partnership with Cambodian Living Arts and others. I’m planning on bringing Royce with me, and spending time meeting new people, such as musicians, artists, survivors. I’ll also be continuing some of my own research on the ground, and continuing conversations with my family. From there, Royce and I plan to build the experience into additional scenes. These relationships and the projects that surround them take years to build, but I’m eventually looking to develop it into a full-length opera.

Showcase Series: Asian Heritage Month continues on Tuesday, May 17 with Ancient Rhythms | Future Echoes, an exploration of Japanese folk drumming. Register today!

Bio:JUNO Award-winning composer Vivian Fung has a unique talent for combining idiosyncratic textures and styles into large-scale works, reflecting her multicultural background. NPR calls her “one of today’s most eclectic composers.” Highlights of recent and upcoming performances include world premieres for Edmonton Opera, Tangram Collective, Vancouver Symphony Orchestra, Ensemble for These Times, trumpeter Mary Elizabeth Bowden, Toronto Symphony Orchestra, American String Quartet, and many more. Passionate about fostering the talent of the next generation, Fung has mentored young composers in programs at the American Composers Forum, San Francisco Contemporary Chamber Players, San José Youth Chamber Orchestra, and Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary Music. Born in Edmonton, Canada, Fung received her doctorate from The Juilliard School. She currently lives in California and is on the faculty of Santa Clara University. Learn more at www.vivianfung.ca.